Energy for what? Aalto Sustainability Talks 27 November: slides, text and video

The topic of November’s Aalto Sustainability Talks online seminar was United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7), which is Access to affordable and clean energy for all. Obviously, SDG7, by definition, concerns 2.7 billion people i.e. 40% of global population not having this type of access. Most of them live in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia.

Here you may find my presentation slides, my 15-minutes talk (in written, because of stage fright I wrote it all down beforehand). Video recording link is available on Aalto University Youtube Channel.

PRESENTATION: Energy for what? A look at users, uses, needs and solutions.

SLIDE 1

Hi everybody! I was invited to say something about our research in India. A couple of years ago, I researched solar power use, in very small scale, in rural India. For more information of those studies, please refer to my website. Because today I will focus on energy for cooking. The name of my presentation is broad, and more like a slogan, actually. I chose this name simply because I see there is a great need for more look at users, uses, and in more taking culturally sensitive approaches. Only after that solutions shall arrive.

Hi everybody! I was invited to say something about our research in India. A couple of years ago, I researched solar power use, in very small scale, in rural India. For more information of those studies, please refer to my website. Because today I will focus on energy for cooking. The name of my presentation is broad, and more like a slogan, actually. I chose this name simply because I see there is a great need for more look at users, uses, and in more taking culturally sensitive approaches. Only after that solutions shall arrive.

SLIDE 2

To this slide I have collected some pictures of situations where energy is being used in rural India. These pictures are mainly from the state of Uttar Pradesh. Actually, I am very happy for this opportunity to be presenting here, because I got to make this gallery. It is not a comprehensive collection of every energy practice there is. As a matter of fact, it just shows a great pluralism in energy uses in rural areas. Here we find, for example

To this slide I have collected some pictures of situations where energy is being used in rural India. These pictures are mainly from the state of Uttar Pradesh. Actually, I am very happy for this opportunity to be presenting here, because I got to make this gallery. It is not a comprehensive collection of every energy practice there is. As a matter of fact, it just shows a great pluralism in energy uses in rural areas. Here we find, for example

- manual power for water access. Also diesel pumps for water access

- small motorcycle battery for lighting

- again manual work for masala grinding, and preparing okra

- there is grid electricity for masala grinding (the mixer on the left, 420 W of power)

- kerosene lanterns and solar power for lighting

- solar home system for running a radio

- chulha stoves for cooking

- dry leaves for water heating

During my field trips 2015 — 2018 I observed, that with increasing income, more energy sources a family normally had. The picture on the right demonstrates a more wealthy family possessing three power system connections: 1: Indian national grid connection, used e.g. for a mixer; 2: local energy entrepreneurs solar-micro grid; and 3: private solar home system. All of these systems serve different purposes. I would like to pose the question:

- Do the people in these pictures have energy access? To me it shows they do. At least to some extent.

- Do the people have CLEAN energy access? Not always.

Dirtiest here are probably the diesel-run water pumps and kerosene lanterns, that are widely utilized. Also because reliable grid power is not available for everybody. But let’s take some moments with the traditional cooking stoves, the chulhas. Because it is the most popular technology for cooking in these areas.

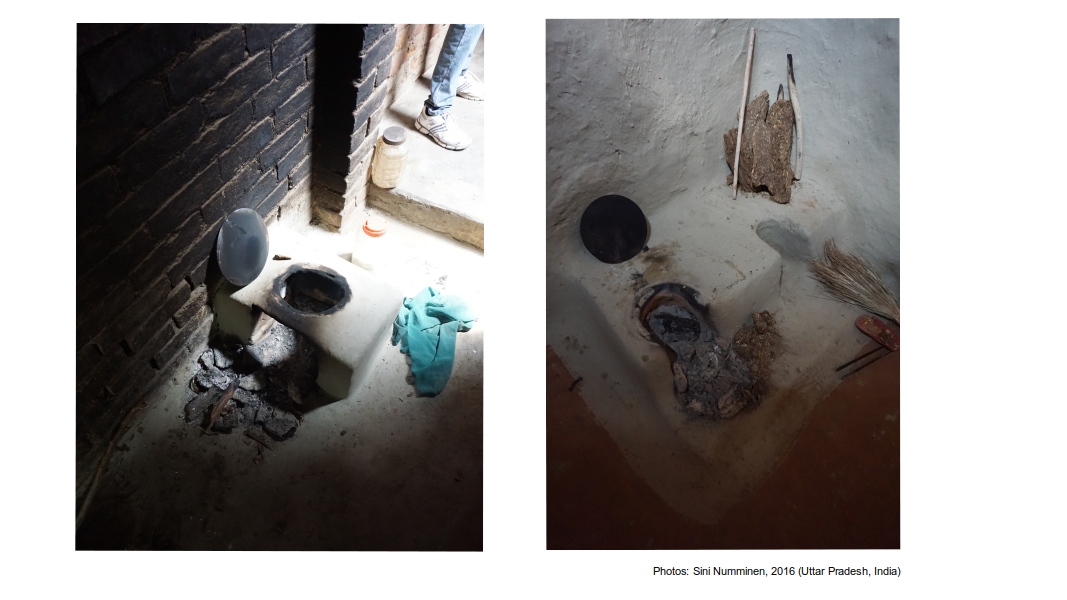

SLIDE 3

I have taken this picture near Unnao in Uttar Pradesh. From an outdoor kitchen in a rural hamlet (small village). The chulha cooking tradition has been in India maybe at least 4000 years. There is evidence them being in use 1800 BCE. The stoves are typically made out of mud or clay. Often women manufacture them. They come in all shapes, designs and sizes. Many families in rural India have one or more stoves like this.

There has been many Improved Chulha programmes in India. But the position of Chulha remains. For example, The Indian government tried, in a large programme in the 1980s to replace these stoves by disseminating millions of new “improved” stoves, but none of them was eventually in use when the programme ended twenty years later [1]. This picture is from an outdoor kitchen. As fuel serves buffalo dung cakes dried. The dung is an never-ending resource especially if you have a buffalo or a cow. It is free of charge, and therefore relevant for many low-income families.

SLIDE 4

These images are from indoor kitchens. First thing we observe is that in the kitchen on the left, the smoke has coloured the walls. The stove on the right, on the other hand, is probably a bit better designed as there is also a chimney integrated. Its usage is not so harmful for women and children who are typically exposed to smoke. I don’t know whether the stove on the right is counted as an improved cookstove (ICS) that would meet the criteria of clean energy. Probably not.

Importantly, chulhas often also serve as indoor heating devices. In Northen India the winters can be cold. With chulhas also water gets heated up and indoor spaces ligtened up. So how can you tell a family to replace such a multi-purpose device? Regarding cooking, it is also about traditions and practices. Anybody doing cooking knows it’s not firstly about the amount of fuel (energy efficiency is typically the main target of ICS programmes). It’s about the pans and the pots, how they can be used, their sizes and the delicate balance with temperature and timing. The taste of good food is a combination of all that. Art of cooking comes with time and skill.

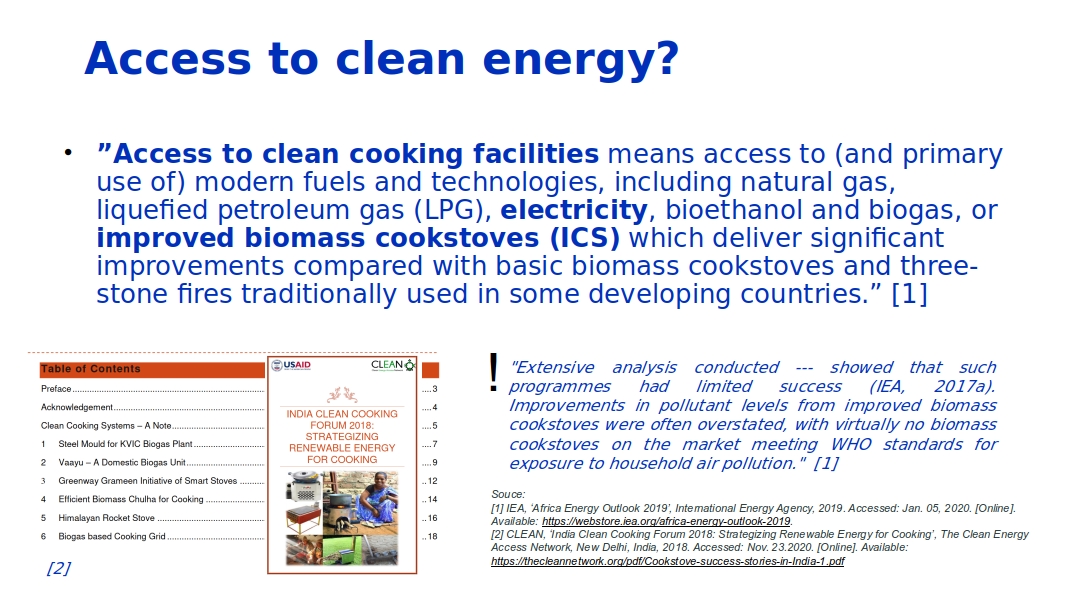

SLIDE 5

But by definition, these people who are using these stoves, do not have access to clean cooking facilities. They have dirty facilities. CLEAN energy means, that you can cook with biomass, but you need to have some IMPROVEMENTS, meaning a so called Improved Cooking Stove (ICS). Traditional cooking does not go. In this slide there is the official definition. It says, that access to clean cooking facilities means primary use of modern fuels, including LPG, electricity, biogas, and improved biomass cookstoves (ICS) [2]. That’s what is says there.

But what is very worrisome is that according to the International Energy Agency, there currently are no “improved cookstoves” available in the market! The ones that call themselves improved, are not improved in terms of their particle emissions [2]. Quote: “Several programmes support the diffusion of improved biomass cookstoves. Nonetheless, extensive analysis conducted by the IEA for Energy Access Outlook 2017, in collaboration with the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, showed that such programmes had limited success (IEA, 2017a). Improvements in pollutant levels from improved biomass cookstoves were often overstated, with virtually no biomass cookstoves on the market meeting WHO standards for exposure to household air pollution.”[2] !

To me this official definition doesn’t look 100% clean either, in the purest meaning of the word CLEAN. Because there is also the diesel electricity and coal electricity included. But let’s not go into that, today.

SLIDE 6

However, under this category of “not having access to clean cooking facilities” we are talking about a great number people with a great variety of backgrounds, kitchens, practices and social and economic realities. Globally, there are 2.7 billion people without access to “modern and clean cooking fuels”, i.e. mainly cooking with solid biomass in traditional stoves. That’s about 40% of global population which is a lot! My source for the numbers is UNDP last week [3]. In India, this definition is fulfilled by 680 million people which is over half (57%) of Indian people. There is no other country in the world ihabiting such a huge population “without access to clean cooking”.

Quote: “In 2018 an estimated 680 million people in India still do not have access to clean cooking solutions and primarily rely on biomass for cooking (IEA, 2018b). Based on stated policies, IEA projections indicate that the share of the population relying on the use of traditional biomass for cooking will continue to decline, dropping initially to around 500 million, a third of population in 2030, and a quarter by 2040. In spite of this progress, traditional cooking still imposes a substantial burden on women, in particular, who spend on average nearly 1.5 hours per day collecting fuelwood, equivalent to more than 100 billion lost working hours (IEA, 2017b).” [4]

This photograph is taken in a village in Norhern India. The 680 million does not mean that there are 680 million Indians in living in such villages. There is also urban energy poverty, where energy access problems are very different. Energy access problems can be found in every Indian state, but particularly in few states in the north.

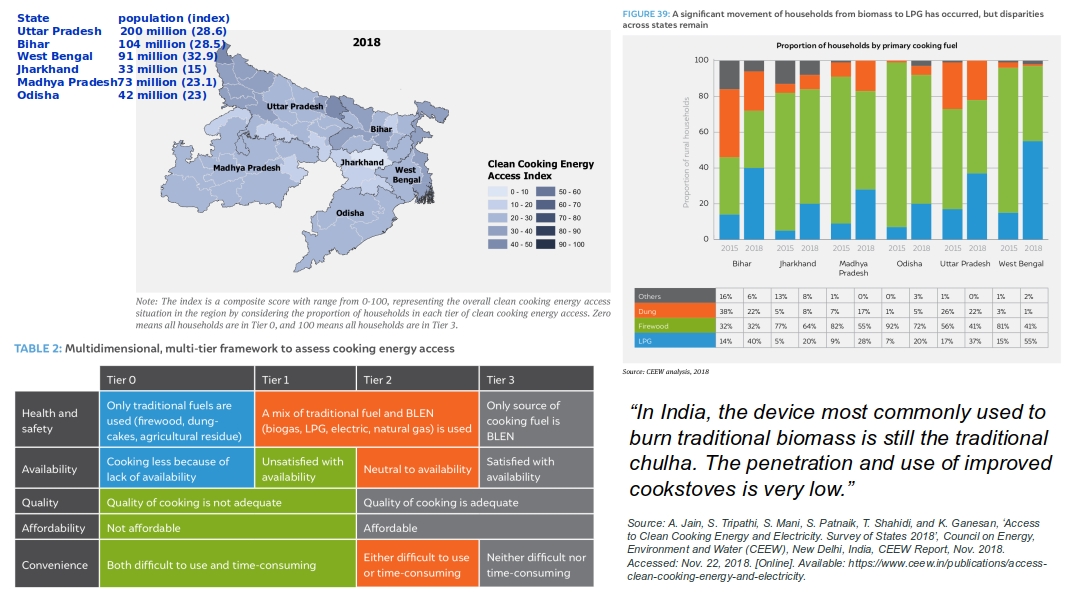

SLIDE 7

Here are some details on clean cooking facility access from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal, that are probably the most energy poor states of India. The orange and green bars on the right demonstrates that the position of solid biomass is persistent. This data is based on a large ACCESS study, where they surveyed tens of thousands of people door-to-door.[5]

Even though the Government of India has provided subsidized LPG and kerosene for households since early 2000, the position of traditional cooking has not been overruled [6]. There has been a decrease of only a couple of % in terms of share of population using solid biomass as their primary cooking fuel. The government programme does boost the use of LPG and kerosene, but people stack it, because LPG is more expensive, than biomass. This phenomenom is called “stacking”. LPG is not used daily, but in special occasions only.

What is interesting in this data is, that the authors [5] count an index for energy access. The index is not only binary: access versus no-access. They include some qualitative criteria, like quality and convenience, which is a very welcomed approach, mainstreamed not long time ago. There is an ongoing debate on definitions and also critical views on how to categorize, or whether and what to categorize [7].

SLIDE 8

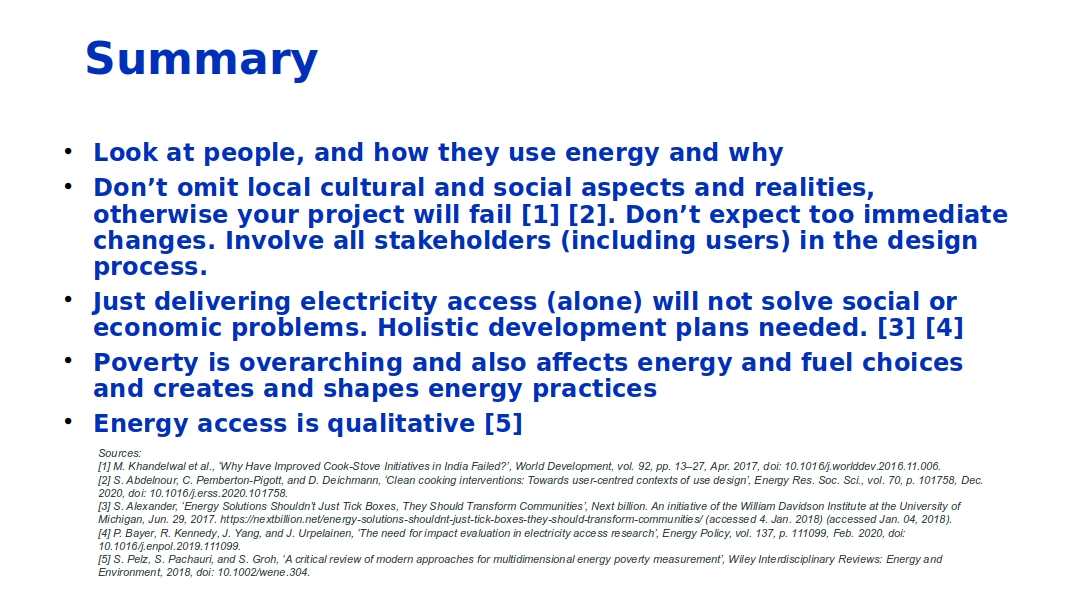

This 15 minutes was too short to give a profound analysis on the reasons why the improved chulha programmes failed. But as a summary I made some reading collection, and give some suggestions for those inspired in involving themselves into programmes for increasing access to clean energy. One of the references (number 1 on the slide), for example, gives a nice overview of reasons why it is so difficult to intervene and “disseminate”, to use the horrible word, some new technology in a foreign location. Five key reasons listed are 1) mismatch between goals of rural people and the programm promoters; 2) technical no-so-good design 3) functional not-so-good design, i.e. new stoves require a complete lifestyle and cultural and social and behavioural change 4) underestimation of the value and multipurpose role of chulha 5) program organisation and coordination related problems of programs that are typically foreign-led by NGOs, philantro-capitalists, international development organisation, corporations, universities etc [8].

Quote: “Clean cookstove interventions largely fail to achieve their stated aims. In our view, the underlying flaw of many cooking interventions is a systemic lack of attention to users’ rank ordering of product features and contexts of use during the product design process. Drawing on examples of cookstove and product design, together with our experience in cookstove design, research and product standards development, we offer four suggestions for improving cookstove interventions. – – – We conclude with a call for an inclusive approach to designing cookstove interventions that is centred around the lived experiences of users and rooted in context-specific knowledge.” [8]

Quote: “This singular focus may be the problem. What if we were to change track and work with rather than against rural women’s clear preferences and were to make LPG affordable and available, or, alternatively, seek a more gradual shift rather than outright replacement of existing technology? What if cookstove improvements were seen as additions to rather than replacements of existing chulhas, a situation often called ‘‘stove stacking” (Subramanian, 2015, p. 155). Gradual and additive technological transitions may be more common than outright substitutions.” [1]

REFERENCES

[1] M. Khandelwal et al., ‘Why Have Improved Cook-Stove Initiatives in India Failed?’, World Dev., vol. 92, pp. 13–27, Apr. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.006.

[2] IEA, ‘Africa Energy Outlook 2019’, International Energy Agency, 2019. Accessed: Jan. 05, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://webstore.iea.org/africa-energy-outlook-2019.

[3] UNDP, ‘Goal 7: Affordable and clean energy’, UNDP. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-7-affordable-and-clean-energy.html (accessed Nov. 18, 2020).

[4] IEA, ‘India 2020 - Energy Policy Review’, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2020-01/IEA-India%202020-In-depth-EnergyPolicy.pdf.

[5] A. Jain, S. Tripathi, S. Mani, S. Patnaik, T. Shahidi, and K. Ganesan, ‘Access to Clean Cooking Energy and Electricity. Survey of States 2018’, Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), New Delhi, India, CEEW Report, Nov. 2018. Accessed: Nov. 22, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.ceew.in/publications/access-clean-cooking-energy-and-electricity.

[6] P. Choudhuri and S. Desai, ‘Gender inequalities and household fuel choice in India’, J. Clean. Prod., vol. 265, p. 121487, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121487.

[7] S. Pelz, S. Pachauri, and S. Groh, ‘A critical review of modern approaches for multidimensional energy poverty measurement’, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ., 2018, doi: 10.1002/wene.304.

[8] S. Abdelnour, C. Pemberton-Pigott, and D. Deichmann, ‘Clean cooking interventions: Towards user-centred contexts of use design’, Energy Res. Soc. Sci., vol. 70, p. 101758, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101758.